1

November 2021

Sustaining the Good Life:

SNAP in Nebraska

\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

Sustaining the Good Life:

SNAP in Nebraska

About OpenSky Policy Institute

Our mission is to improve opportunities for every Nebraskan by providing

impartial and precise research, analysis, education and leadership.

November 2021

OpenSky Policy Institute is supported by generous donors. This primer could not have been

completed without their support.

Staff

Renee Fry — founding executive director of OpenSky Policy Institute

Chuck Brown — deputy director

Tiffany Friesen Milone — editoral director

Connie Knoche — education policy director

Nyomi Troy Thompson — health policy analyst

Craig Beck — senior scal analyst

Laurel Sariscsany — policy analyst

Toni Roberts — operations manager

Technical Advisors

Ken Smith, Staff Attorney - Economic Justice Program, Nebraska Appleseed

Shelley Mann, Assistant Director of SNAP, Food Bank for the Heartland

Jennifer Carter, Inspector General for Child Welfare, State of Nebraska

Contributors to this primer include Tiffany Friesen Milone, Mary Baumgartner, Nyomi Troy Thompson,

Chuck Brown and Renee Fry.

Any portion of this report may be reproduced without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

OpenSky Policy Institute, Sustaining the Good Life: SNAP in Nebraska, OpenSky Policy Institute,

2019, updated 2021.

To download a copy of this primer, please go to www.openskypolicy.org. To obtain a printed copy or for

other information, please contact:

OpenSky Policy Institute

1327 H Street, Suite 102

Lincoln, NE 68508

402.438.0382

Acknowledgements

\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

What is SNAP? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

How Does SNAP Work?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

Who is Eligible? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Length of Enrollment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Disaster Relief . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Safeguards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

SNAP as a Long-Term Investment . . . . . . . . . 8

SNAP and Businesses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

SNAP and Workers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Table of Contents

\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

3

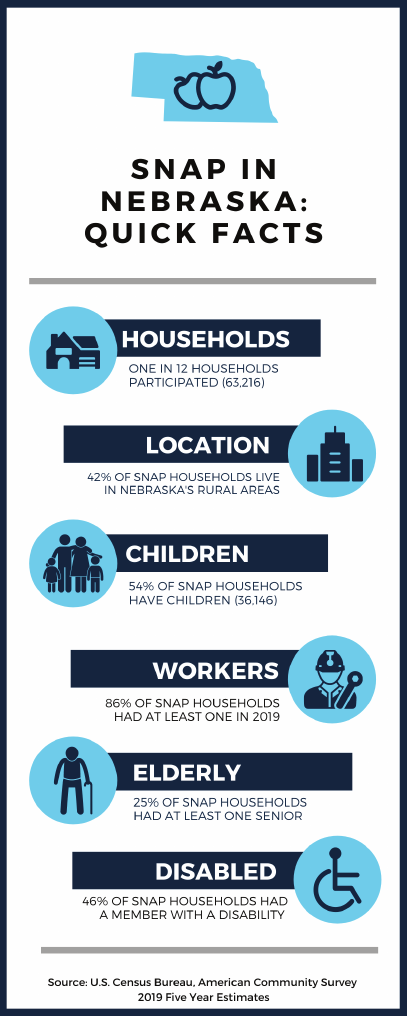

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is Nebraska’s most important anti-hunger

program, helping more than 160,000 Nebraskans afford quality food

1

. In addition to helping lift

people out of poverty, SNAP is considered the most effective form of stimulus during an economic

downturn and each dollar of benets redeemed has the potential to multiply through the supply

chain, strengthening the state’s businesses

2

. Furthermore, studies have shown that childhood

exposure to SNAP leads to increased economic self-sufciency in adulthood and less reliance on

similar government programs.

What is SNAP?

SNAP, formerly called Food Stamps, is a program

providing important nutritional support for low-wage

working families, low-income seniors and people with

disabilities living on xed incomes, and other low-

income families and individuals. The federal government

pays the full cost of SNAP benets and splits the cost

of administering the program with states. In Fiscal Year

2019 (FY19), more than $220 million in SNAP benets

were issued to Nebraska residents at a cost to the state

of $19 million

3

.

Food Stamps began during the Great Depression,

when the government offered orange stamps for sale,

pricing them roughly equal to what families would

normally spend on food

4

. For every dollar of orange

stamps bought, $0.50 of “bonus” blue stamps were

also received. Orange stamps could buy any type of

food while blue stamps were limited to “surplus” foods,

as identied by the U.S. Department of Agriculture

(USDA). This program ran from 1939 to 1943, when it

was determined that “the conditions that brought the

program into being -- unmarketable food surpluses and

widespread unemployment -- no longer existed.”

5

The program in its current form began in 1961 with

President John F. Kennedy’s rst executive order,

which created pilot programs in eight counties with

the stated intention of “increasing the consumption of

perishables.”

6

The program was expanded signicantly

by President Lyndon B. Johnson, who gave all counties

the authority to launch their own Food Stamp programs

in 1964. Participation was optional until 1974, although

by that point 90 percent of the population were already

living in participating counties. In 1977, the requirement

that participants make a purchase in order to receive

a benet (the so-called “purchase requirement”) was

eliminated

7

. From that point on, participants received

Introduction

\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

4

the formerly free portion of their benet in coupons but were

expected to continue buying healthy food by supplementing

those coupons with cash. This led to the current formula,

which assumes a household can spend 30% of its net income

on food (explained in more detail below).

Several additional changes have been made over the years,

largely aimed at streamlining processes, reducing the

potential for fraud and encouraging participants to work or

nd higher paying jobs. One major change was the adoption

of Electronic Benets Transfer (EBT), a system allowing

recipients to authorize a transfer of their government benets

from a federal account to a retail account to pay for groceries,

which began as a pilot program in 1984 and spread to all 50

states by 2004. This system is more efcient to administer and

cut back on fraud by creating an electronic record of each

transaction, making it easier to identify violations.

Most recently, the USDA reevaluated how it calculates a

“thrifty” food plan, which serves as the basis for SNAP benet

allotments, as directed by the 2018 Farm Bill

69

. As a result,

a family of four could receive almost $5 a day in additional

benets starting in October 2021.

SNAP is reauthorized by the Farm Bill roughly every ve years

and is run by the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service

8

. The

thrifty food plan calculation also will be evaluated annually by

the USDA going forward.

How does SNAP Work?

SNAP is intended to ll the gap between the cash a

household has available to buy food and the cost of a thrifty

food budget

9

.

A household with no income would receive the full cost

of a thrifty food budget, known as the “maximum allotment.” As household income increases, the

household is expected to contribute more of its own resources to food and SNAP benets decrease

accordingly. Benets decline gradually – so for every $1 of added income, a household’s benets go

down by $0.24 to $0.36.

SNAP CALCULATION

FOR A FAMILY OF FOUR

WITH $800 NET

MONTHLY INCOME

(TWO ADULTS AND TWO TEENAGED CHILDREN)

Maximun

Monthly

Allotment

$835

30% of

Net Monthly

Income

(.30 x $800) =

$240

SNAP

Monthly

Benefit

$595

5

This means a family of four – two adults and two teenaged children – with a net monthly household

income of $800 would receive $595 per month in SNAP benets in scal year 2021, or $6.61 per person

per meal (assuming a 30-day month and three meals a day).

Nebraska’s benets are distributed via an EBT system managed by the vendor Fidelity Information

Services

10

. EBT cards function like debit cards and can be used at authorized retailers to purchase

approved food items

11

. Approved food items include fruits, vegetables, meat, dairy products, breads,

snack foods and non-alcoholic beverages, as well as seeds

and plants to grow food

12

. Non-approved items include

alcohol, cigarettes and nutritional supplements

13

. If a

household doesn’t use all of its monthly benets, they can

roll them over for up to a year

14

.

Who is Eligible?

SNAP benets are broadly available to those with low

incomes. Eligibility rules and benet levels are generally set

at the federal level, although states have some exibility in

tailoring the program.

There are two pathways for eligibility: traditional eligibility,

under which a household must meet program-specic

eligibility rules; and categorical eligibility, under which

a household becomes automatically, or “categorically,”

eligible by being eligible for or receiving benets from

another low-income program

15

.

Traditional eligibility uses income and asset tests to

determine if a household qualies. Households with a

member over 60 or who is disabled must have a net monthly

income at or below 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and have less than $3,500 in liquid assets, such

as cash on hand or anything that could be readily sold for cash

16

.

Households without an elderly or disabled member must not only meet the net income test, but also have

a gross monthly income at or below 130% of the FPL

17

and have less than $2,250 in liquid assets, excluding

the value of their home, any retirement or educational savings and a portion of a vehicle’s value

18

.

Categorical eligibility eliminates the requirement that households that have already met the nancial

eligibility rules for a different low-income program such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

19

or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

20

must also go through a separate eligibility

determination for SNAP

21

.

GROSS INCOME

versus NET INCOME

GROSS INCOME

The amount of money a household

takes home before deductions.

NET INCOME

Gross income minus:

• 20% earned income deduction

• $160 standard deduction

• Dependent care deduction

• Medical expenses for elderly/disabled

• Excess shelter costs

(more than 50% of net income)

100% of FPL

$2,092

Households without

an elderly or disabled

member must also have

gross income

below 130% FPL

All households must

have net income

below 100% FPL

165% of FPL

$3,644

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture

MONTHLY

INCOME THRESHOLDS

for a FAMILY OF FOUR

6

TANF participants may be categorically eligible for SNAP despite the fact that some states make certain

TANF benets available to people with higher incomes or greater assets than allowed under traditional

SNAP eligibility rules

22

. Under a policy known as “broad based categorical eligibility” (BBCE), states are

given the choice of expanding categorical SNAP eligibility to households with incomes up to 200% of

the FPL, or $4,367 a month for a family of four in 2020, which is the maximum threshold for any TANF

benet, with the federal government continuing to pay the full cost of benets issued

23

.

In Nebraska, BBCE is used raise the asset test threshold for households referred to SNAP through a

state program called the Expanded Resource Program

24

. Households referred by the program must still

have gross incomes at or below 130% of the FPL, but can have up to $25,000 in liquid assets and still be

eligible

25

. Forty-two states have some form

of BBCE, although Nebraska is one of six

that impose an asset limit on it

26

.

In 2021, Nebraska also used BBCE to raise

the net income limit from 130% of the FPL

to 165%, although households must still

have gross incomes less than 100% of the

FPL and meet the other asset tests

27

. The

increase will sunset September 30, 2023.

There are some categories of people that

won’t be eligible for SNAP regardless of

their income or assets, including those

convicted of certain drug-related felonies,

employees on strike, most college students,

undocumented immigrants and some legal

immigrants

28

.

Length of Enrollment

There are no limits on the length of SNAP enrollment for most participants: the elderly, people with

disabilities, pregnant women and those with dependent children

29

. All households must reapply for

benets every six months and report any income changes that would affect their eligibility as the

changes arise

30

.

Able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWD) aged 18 to 49 are generally limited to three months

of benets in any 36-month period when they aren’t employed or participating in a qualifying workforce

or job training program for at least 20 hours a week

31

.

During periods of high unemployment when qualifying jobs may be hard to nd, states may apply for

a waiver of the three-month time limit for specic areas

32

. States must demonstrate that the target

location has an insufcient number of jobs or an unemployment rate over 10%

33

. If granted, the three-

month limit is suspended until the waiver ends, usually a year later, although it could be two years in

areas of chronic high unemployment or job insufciency

34

. The federal government continues to pay the

full cost of benets provided during the waiver period.

During the Great Recession, the federal government suspended the three-month time limit for part

of 2009 and 2010, allowing states to keep the limit only if they also provided workforce or job training

to anyone affected. States did not have to request a waiver, so most states, including Nebraska,

operated under waivers during the recession and its aftermath

35

. Similarly, in response to the 2020

pandemic, the federal government enacted the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which

waived the three-month limit from April 2020 through the month after the COVID-19 public health

emergency declaration has been lifted

36

.

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Fiscal Year 2019. Note: this data

predates the change to the thrifty food budget discussed above and so these

numbers will increase significantly once that change is fully implemented.

$242

Average SNAP

benet per

household per

month

$124

Average SNAP

benet per

person per month

$1.26

Average SNAP

benet per

person per meal

7

As of FY 2021, 24 states, including the District of Columbia, had a full waiver, ve had a partial waiver,

and 22, including Nebraska, had no waiver

37

.

Disaster Relief

The federal government also offers what’s called the Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program (D-SNAP) to expand eligibility to individuals and communities impacted by a major disaster.

The President can issue a Major Disaster Declaration after any event that stresses local government

resources to the point where federal intervention is necessary, including tornadoes, severe storms,

ooding and pandemics. After the declaration is made, states can apply to the USDA for D-SNAP

38

.

If granted, D-SNAP expands income eligibility beyond that of the traditional SNAP program, allowing

an entire month of food assistance to reach impacted families who wouldn’t otherwise be eligible. The

D-SNAP benet amount equals the maximum allotment determined under traditional SNAP guidelines

and is standardized to provide equal amounts to those families qualifying under D-SNAP and those who

were receiving SNAP prior to the declaration

39

.

Since 2017, the USDA has approved D-SNAP issuance to 13 states, including Nebraska

40

. In March 2019,

a Major Disaster Declaration was issued in the wake of ooding caused by a severe winter storm, making

D-SNAP available in 27 counties

41

. Around $3.5 million of benets were issued throughout the affected

areas

42

, producing an estimated $5.95 million in economic activity

43

.

Safeguards

SNAP has a rigorous upfront eligibility determination system to ensure program efciency and integrity.

To apply, households report income and other information that is veried by a state eligibility worker

through interviews with a household member, data matches and documentation provided by the

household or another party, such as an employer or landlord

44

.

Policymakers at both the state and federal levels have long been focused on reducing fraud and

improving payment accuracy

45

. These efforts generally target four types of inaccuracy or misconduct:

• Trafcking, which is the illicit sale of benets and can involve retailers and participants;

• Retailer application fraud, which involves an illicit attempt by an ineligible retailer to

participate in the program;

• Errors and fraud by applying households, with errors considered unintentional and fraud

considered intentional; and

• Errors and fraud by state agencies, which result in improper payments and involves

state quality control systems.

Fraud is “relatively rare” within the program

46

. The most common measure is the national retailer

trafcking rate, which is released about every three years and most recently estimated 1.5% of SNAP

benets redeemed from FY12 to FY14 were trafcked. A review of the USDA’s State Activity Report from

2016 – the most recent year available – concluded that most overpayments resulted from error rather

than fraud: about 62% from recipient error, 28% from agency error and 11% from recipient fraud

47

.

To prevent fraud and over- or underpayment, states are required to conduct a monthly audit of their

programs through a SNAP quality control system. This involves independent state reviewers checking

the eligibility and benets decisions made in a representative sample of SNAP cases. Federal ofcials

8

then re-review a subsample of the reviewed cases and release payment error rates based on the reviews.

States may be penalized if their error rates are repeatedly above the national average

48

.

SNAP as a Long-Term Investment

A recent comprehensive study

49

found that childhood exposure to SNAP benets “reduces the

likelihood that individuals receive income from public programs in adulthood.” The implication,

therefore, is “that the social safety net for families with young children may, in part, ‘pay for itself’ by

reducing reliance on government support in the long-term

50

.”

Researchers looked at data on 43 million Americans to track the long-term impacts of childhood

exposure to Food Stamps and SNAP on adult economic productivity and well-being

51

. They linked

Census data to data from the Social Security Administration to track children from SNAP-enrolled

families through adulthood and found that those exposed in utero through age ve were more likely to

live longer, be economically self-sufcient and own their own home and less likely to be incarcerated

52

.

This study conrmed prior research showing access to nutritional support programs early in life

improves economic self-sufciency in later life, especially for women. In households with young children,

the study’s authors found, SNAP “is the opposite of ‘welfare trap.’”

53

Providing critical benets to

children at pivotal developmental stages “apparently allows them to invest in the skills that, in turn, will

enable them to escape poverty when they grow up

54

.”

SNAP and Businesses

SNAP also is an important public-private partnership. In addition to helping families afford a basic diet,

it generates business for retailers and boosts local economies. To participate, retailers must stock a

prescribed variety of foods and have applied for and received authorization from the USDA. There are

1,290 authorized retailers in Nebraska, ranging from farmer’s markets and butchers to national chain

superstores, that redeemed roughly $222 million in benets in 2019

55

.

According to Moody’s Analytics, $1 in SNAP spending generates about $1.70 in economic activity during

a weak economy

56

. This means the $222 million received by retailers in 2019 would have generated $377

million in overall economic activity for Nebraska were the

state in an economic downturn. This is called a “multiplier

ef fec t.”

How does the multiplier effect work? In an economic

downturn, many households have less money to spend,

causing business at local stores and restaurants to slow. These

businesses then also have less money to spend, furthering the

downturn. To weather the downturn, some households may

enroll in SNAP, which gives them more money to spend at the

local grocery store. Every dollar spent there helps the store

recover. More revenue means the store can hire back staff,

make improvements and purchase more food from farmers

and distributors to meet increased demand. As the increased

spending from SNAP ows through the economy, each sector

receiving a share of that additional money is able to spend

more money.

The social

safety net for

families with

young children

may, in part,

‘pay for itself’

by reducing

reliance on

government in

the long-term.

9

Because households are able to redeem their monthly SNAP benets quickly, the program is one of the

most effective forms of stimulus during an economic downturn

57

. In fact, a May 2019 study by the USDA

looked at the impact of SNAP redemptions on county-level employment and found that, during the

Great Recession, one job was created for every $10,000 in SNAP benets redeemed within rural counties

(the impact was smaller in metropolitan counties)

58

. Further, because SNAP benets can only be spent

on food, money may be freed up for these households to spend on other goods and services at local

businesses, helping them recover and raising sales tax revenue for state and local government entities.

SNAP and Workers

Each state is required to administer a SNAP Employment & Training Program, with the federal

government matching 50% of the program’s cost

59

. Nebraska has the Next Step Employment & Training

(E&T), which is a collaboration between the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the

Department of Labor. It offers job search and resume assistance, interview training, vouchers to buy

interview clothing and childcare and other services and is available to SNAP households with: no more

than four people; a worker or someone recently unemployed (within 90 days); and at least one work-

eligible member (a legal permanent resident or citizen)

60

. The program is currently only available to

participants residing in or around Kearney, Columbus, Grand Island, North Platte, Scottsbluff, Sidney,

Lexington, Norfolk, Hastings and Omaha, , with expansion to Lincoln in the works

61

.

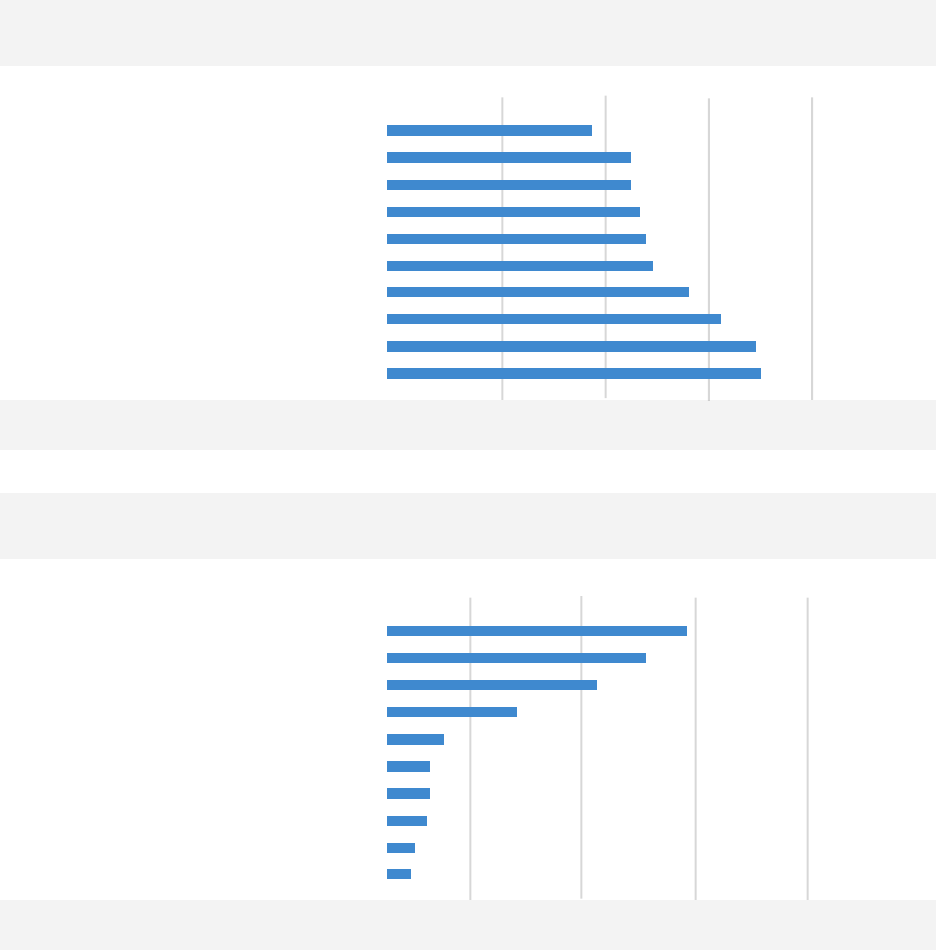

However, many Nebraskans who receive SNAP are already working: 86% of SNAP households had at

least one member working and 32% had at least two members working in 2019

63

. A signicant share

of workers participating in SNAP work in service industries such as retail, hospitality and home health.

These types of jobs are likely to have low wages (see below), few benets and unpredictable or seasonal

hours. SNAP can supplement low and uctuating pay and help workers get by during periods of

unemployment or limited hours.

THE MULTIPLIER EFFECT

10

SNAP is structured – and funded – as an entitlement program, meaning that anyone who meets the

eligibility criteria can participate

64

. This allows most workers with uctuating incomes to regain access to

benets quickly during downswings. Other programs, such as child care or housing assistance, are often

subject to funding limitations that lead to long wait times. A worker may therefore be reluctant to accept

a raise or additional hours that could render them ineligible because they may not be able to reenroll

quickly in those programs if circumstances change. SNAP is structured to avoid this dilemma.

5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000

TOTAL WORKERS ON SNAP BY INDUSTRY

Accommodation and Food Services

Healthcare and Social Assistance

Manufacturing

Construction

Educational Services

Transportation and Warehousing

Finance and Insurance

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation

Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting

Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services

SAMPLE WAGES BY OCCUPATION Median Hourly Wage

The program also gives workers preferential treatment, allowing a deduction for earned income – but

not for unearned income – from the net income calculation

65

. This means a household with workers

will receive a larger SNAP benet than a same-sized household with income from unearned sources.

Benets also phase out slowly as incomes rise, so most households will see an increase in their total

income – earnings plus SNAP benets – when their earnings go up modestly.

$

Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Employment

and Wage Statistics,” May 2020, accessed at https://www.

bls.gov/oes/2020/may/oes_ne.htm on Dec. 6, 2021.

$5.00 $10.00 $15.00 $20.00

Waiters and Waitresses

Childcare Workers

Cashiers

Maids and Housekeeping Cleaners

Retail Salespersons

Home Health and Personal Care Aides

Farmworkers and Laborers

Slaughterers and Meat Packers

Light Truck Drivers

Construction Laborers

11

Some households, however, may face a benet “cliff” if an increase in earnings puts them over the

income limit

66

. Once earnings exceed the limit, even by a little bit, a household loses eligibility in the

program. If the increase was less than what the household was receiving in benets, their total income

will decrease and the household becomes worse off despite the added income.

In an attempt to counteract the “cliff effect,” more than 40 states use categorical eligibility to smooth

the transition for these households by raising the income limit, allowing them to accept higher paying

work or increased hours without losing their eligibility

67

. Nebraska has used BBCE to raise asset limits

and, more recently, to increase the net income limit to 165% of the FPL through September 30, 2023

68

.

This will ease the cliff effect for many families, but is temporary and well below the 200% limit set by

many other states using their BBCE authority.

Conclusion

The benets of SNAP participation for low-income families are extensive and well documented,

as is the program’s potential to help communities recover during economic downturns. These make the

program a sensible, long-term investment for the state and its residents.

1 U.S. Census Bureau, 2019, 5-year ACS estimates.

2 Hilary Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach and Douglas Almond, “Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,”

American Economic Review (106)4, April 2016, pp. 903-934, https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/Hoynes-

Schanzenbach-Almond-AER-2016.pdf (accessed August 15, 2019).

3 Data obtained directly from Nebraska’s Legislative Fiscal Ofce in August 2019.

4 U.S Department of Agriculture (USDA), “A Short History of SNAP,” https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/short-history-snap (accessed

August 15, 2019).

5 USDA, “A Short History of SNAP.”

6 USDA, “A Short History of SNAP.”

7 Committee on Examination of the Adequacy of Food Resources and SNAP Allotments; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee on

National Statistics; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council; Caswell JA, Yaktine AL, editors, Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program: Examining the Evidence to Dene Benet Adequacy, Washington (DC): National Academies Press, April

23, 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK206907/ (accessed October 8, 2019).

8 Congressional Research Service (CRS), “2018 Farm Bill Primer: What Is the Farm Bill?” March 8, 2019, https://crsreports.congress.

gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11126 (accessed August 27, 2019).

9 Hilary Hoynes and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, “Strengthening SNAP as an Automatic Stabilizer,” The Hamilton Project, May

16, 2019, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/les/HoynesSchanzenbach_web_20190506.pdf (accessed September 9,

2019); USDA, “Ofcial USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Four Levels, U.S. Average,” July 2019, https://fns-prod.

azureedge.net/sites/default/les/media/le/CostofFoodJul2019.pdf (accessed August 27, 2019).

10 Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services (NE DHHS), “Nebraska EBT/Electronic Benets Transfer: Questions and

Answers,” July 2018, http://dhhs.ne.gov/Documents/EBT%20Questions%20and%20Answers.pdf (accessed August 15, 2019).

11 NE DHHS, “Nebraska EBT/Electronic Benets Transfer: Questions and Answers.”

12

12 NE DHHS, “Nebraska EBT/Electronic Benets Transfer: Questions and Answers.”

13 NE DHHS, “Nebraska EBT/Electronic Benets Transfer: Questions and Answers.”

14 NE DHHS, “Nebraska EBT/Electronic Benets Transfer: Questions and Answers.”

15 CRS, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Categorical Eligibility,” updated August 1, 2019, https://fas.org/

sgp/crs/misc/R42054.pdf (accessed August 27, 2019).

16 NE DHHS, “Manual Letter #20-2016,” May 21, 2016, https://sos.nebraska.gov/rules-and-regs/regsearch/Rules/Health_and_

Human_Services_System/Title-475/Chapter-3.pdf (accessed August 15, 2019); see also Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities (CBPP), “A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benets,” updated Sept. 1, 202, https://www.cbpp.org/research/

food-assistance/a-quick-guide-to-snap-eligibility-and-benets#_ftn4 (accessed June 3, 2021).

17 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (U.S. DHHS), Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Poverty

Guidelines: U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines Used to Determine Financial Eligibility for Certain Federal Programs,” January

2019, https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines (accessed August 15, 2019).

18 NE DHHS, “Manual Letter #20-2016.”

19 Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is a federal income supplement program that pays monthly benets to help aged,

blind and disabled people with little to no income meet basic needs, such as food, clothing and shelter. U.S. Social

Security Administration, “Supplemental Security Income Home Page – 2019 Edition,” https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/ (accessed

September 9, 2019).

20 Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is a time-limited program intended to assist families with children when the

parents or others cannot provide for the family’s basic needs. It is funded through grants from the federal government to

states, which have broad exibility in structuring the programs, including the type and amount of assistance payments,

the range of other services to be provided and the rules for eligibility. U.S. DHHS, “What is TANF?” https://www.hhs.gov/

answers/programs-for-families-and-children/what-is-tanf/index.html (accessed September 9, 2019)

21 CRS, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Categorical Eligibility,” updated August 1, 2019, https://fas.org/

sgp/crs/misc/R42054.pdf (accessed August 15, 2019).

22 CRS, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Categorical Eligibility.”

23 CRS, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Categorical Eligibility;” see also U.S. DHHS, “Poverty Guidelines,

all states (except Alaska and Hawaii),” 2020, https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/les/aspe-les/107166/2020-percentage-poverty-

tool.pdf (accessed June 3, 2021.

24 CRS, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Categorical Eligibility.”

25 NE DHHS, “Manual Letter #20-2016.”

26 CRS, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Categorical Eligibility.”

27 Nebraska Legislature, “LB 108,” 2021, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/107/PDF/Slip/LB108.pdf (accessed June 14, 2021).

28 CBPP, “Policy Basics: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP),” updated June 25, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/

research/food-assistance/policy-basics-the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap (accessed August 15, 2019).

29 7 U.S.C. § 2015.

30 NE DHHS, “Manual Letter $20-2016.”

31 CBPP, “Policy Basics: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).”

32 Ed Bolen and Stacy Dean, , “Waivers Add Key State Flexibility to SNAP’s Three-Month Time Limit,” CBPP, updated February 6,

2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/waivers-add-key-state-exibility-to-snaps-three-month-time-limit#_

ftnref1 (accessed August 27, 2019).

33 USDA, Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), “State Options Report: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” options as of

October 1, 2017, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/les/snap/14-State-Options.pdf (accessed August 27, 2019).

34 USDA, Ofce of Inspector General, “FNS Controls Over SNAP Benets For Able-Bodied Adults Without Dependents,”

September 2016, https://www.usda.gov/oig/webdocs/27601-0002-31.pdf (accessed August 27, 2019).

35 CBPP, “Policy Basics: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).”

36 USDA, FNS, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) – Families First Coronavirus Response Act and Impact on Time

Limit for Able-Bodied Adults Without Dependents (ABAWDs), March 20, 2020, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/

les/resource-les/FFCRA-Impact-on-ABAWD-TimeLimit.pdf (accessed June 3, 2021).

13

37 USDA, FNS, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Status of State Able-Bodied Adult without Dependents

(ABAWD) Time Limit Waivers – Fiscal Year 2021 – 1st Quarter,” https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/les/media/le/

FY21-Quarter%201-ABAWD-Waiver-Status%20.pdf (accessed June 3, 2021).

38 U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency, “How a Disaster Gets Declared,” https://www.fema.gov/disasters/how-declared

(accessed June 4, 2021).

39 USDA, FNS, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Disaster SNAP Guidance,” May 18, 2012, https://njcdd.org/

wp-content/uploads/2016/08/d-snap_handbook.pdf (accessed June 4, 2021).

40 USDA, FNS, “State by State FNS Disaster Assistance,” https://www.fns.usda.gov/disaster/state-by-state (accessed June 4, 2021).

41 USDA, FNS, “Nebraska Disaster Nutrition Assistance,” https://www.fns.usda.gov/disaster/nebraska-disaster-nutrition-assistance

(accessed June 4, 2021).

42 NE DHHS, “Connections,” May 2019, https://dhhs.ne.gov/Connections%20Newsletters/May%202019.pdf#search=d%2Dsnap

(accessed June 4, 2021).

43 Kenneth Hanson, USDA Economic Research Service, “The Food Assistance National Input-Output Multiplier (FANIOM) Model

and Stimulus Effects of SNAP,” October 2010, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/44748/7996_err103_1_.pdf

(accessed June 4, 2021).

44 NE DHHS, “Manual Letter $20-2016.”

45 CRS, “Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP),” September 28, 2018, https://www.

everycrsreport.com/les/20180928_R45147_5e64ffb1200ac2d1af10a24d8848a629e5249407.pdf (accessed August 15, 2019).

46 CRS, “Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).”

47 CRS, “Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).”; see also USDA, “Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program: State Activity Report, Fiscal Year 2016,” https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/les/snap/FY16-

State-Activity-Report.pdf (accessed August 22, 2019).

48 USDA, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Payment Error Rates Fiscal Year 2018,” https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/

sites/default/les/resource-les/FY18-SNAP-QC-Payment-Error-Rate-Chart.pdf (accessed August 15, 2019).

49 Martha J Bailey, Hilary Hoynes, Maya Rossin-Slater and Reed Walker, “Is the Social Safety Net a Long-Term Investment? Evidence

from the Food Stamps Program,” Stanford University, University of California-Berkley, and University of Michigan, April 2019,

https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/LR_SNAP_BHRSW_042919.pdf (accessed August 15, 2019).

50 Bailey, et al., “Is the Social Safety Net a Long-Term Investment? Evidence from the Food Stamps Program.”

51 Bailey, et al., “Is the Social Safety Net a Long-Term Investment? Evidence from the Food Stamps Program.”

52 Bailey, et al., “Is the Social Safety Net a Long-Term Investment? Evidence from the Food Stamps Program.”.

53 Testimony of Dr. Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach on the subject of “Nutrition Programs: Perspectives for the 2018 Farm Bill”

before the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry,” September 14, 2017, https://www.agriculture.

senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Testimony_Schanzenbach.pdf (accessed September 9, 2019).

54 Hoynes, et al., “Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net.”.

55 CBPP, “SNAP Is an Important Public-Private Partnership,” https://www.cbpp.org/snap-is-an-important-public-private-

partnership#Nebraska (accessed June 3, 2021).

56 Mark Zandi, “The Economic Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act,” Jan. 21, 2009, https://www.economy.com/

mark-zandi/documents/Economic_Stimulus_House_Plan_012109.pdf (accessed August 19, 2019). This estimate is in line

with modeling done by the USDA’s Economic Research Service in 2010, when the agency found that every dollar of SNAP

benets redeemed grew the gross national product (GDP) by $1.79 during an economic downturn. See Hanson, “The Food

Assistance National Input-Output Multiplier (FANIOM) Model and Stimulus Effects of SNAP.”

57 Zandi, “The Economic Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.”

58 John Pender, Young Jo, Jessica E. Todd and Cristina Miller, “The Impacts of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Redemptions on County-Level Employment,” USDA, Economic Research Service, May 2019, https://www.ers.usda.gov/

webdocs/publications/93169/err-263.pdf?v=1509.3 (accessed August 19, 2019).

59 USDA, FNS, “SNAP Employment and Training,” https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/et (accessed June 3, 2021); see also NE DHHS,

“Request for Applications – Federal Funds,” https://dhhs.ne.gov/Grants%20and%20Contract%20Opportunity%20Docs/

SNAP%20E%26T%202021%20-%20RFA.pdf (accessed June 3, 2021)..

14

60 NE DHHS, “SNAP Next Step And Employment & Training Programs,” http://dhhs.ne.gov/Pages/SNAP-Next-Step.aspx

(accessed August 27, 2019).

61 NE DHHS, “SNAP Next Step And Employment & Training Programs.”; see also NE DHHS, “Request for Applications – Federal

Funds,” https://dhhs.ne.gov/Grants%20and%20Contract%20Opportunity%20Docs/SNAP%20E%26T%202021%20-%20RFA.

pdf (accessed June 3, 2021).

63 U.S. Census Bureau, 2019, 5-year ACS estimates.

64 Elizabeth Wokomir and Lexin Cai, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Includes Earnings Incentives,” Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities, updated June 5, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-supplemental-

nutrition-assistance-program-includes-earnings-incentives (June 5, 2019).

65 Wokomir and Cai, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Includes Earnings Incentives.”

66 Wokomir and Cai, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Includes Earnings Incentives.”

67 Wokomir and Cai, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Includes Earnings Incentives.”

68 Nebraska Legislature, “LB 108,” 2021, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/107/PDF/Slip/LB108.pdf (accessed June 3, 2021).

69 USDA, “Thrifty Food Plan, 2021,” August 2021, accessed at https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/les/resource-les/

TFP2021.pdf (accessed on Sept. 1, 2021).

15

OpenSky’s mission is to improve opportunities for every Nebraskan by providing impartial and precise

research, analysis, education, and leadership.

Board of Directors

Board President

Kathy Campbell resides in Lincoln where she represented District 25 in the Nebraska Legislature

from 2009 to 2017.

Board Secretary and President Elect

Claude Berreckman, Jr, resides in Cozad where he is managing partner in the Berreckman, Davis &

Bazata, P.C. law rm.

Board Treasurer

Tulani Grundy Meadows resides in Omaha where she is a Political Science and Human Relations Skills

faculty member at Metropolitan Community College.

Jerry Bexten resides in Omaha where he has been the Director of Education Initiatives for the

Sherwood Foundation since October 2006.

Miguel Estevez resides in Gretna and is a mental health practitioner with Completely Kids.

Dr. John Harms resides in Scottsbluff. After a 30-year career as president of Western Nebraska

Community College, Dr. Harms retired in 2006 ahead of an eight-year term in the Nebraska Legislature.

Rosemary Ohles resides in Lincoln and serves as a seminar facilitator for the Council of Independent

College’s Program on Presidential Vocation and Institutional Mission.

Judy Pederson resides in North Plate and is the owner of Pro Printing and Graphics.

Erik Reznicek resides in Lincoln where he has been a data analyst lead with Hudl since 2014.

Chris Rodgers resides in Omaha where is the Director of Community and Government Relations

for Creighton University and also the District 3 Representative on the Douglas County Board of

Commissioners.

Sustaining the Good Life: SNAP in Nebraska

\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

16

17

OpenSky Policy Institute

1327 H Street, Suite 102 | Lincoln, NE 68508

402.438.0382 | openskypolicy.org