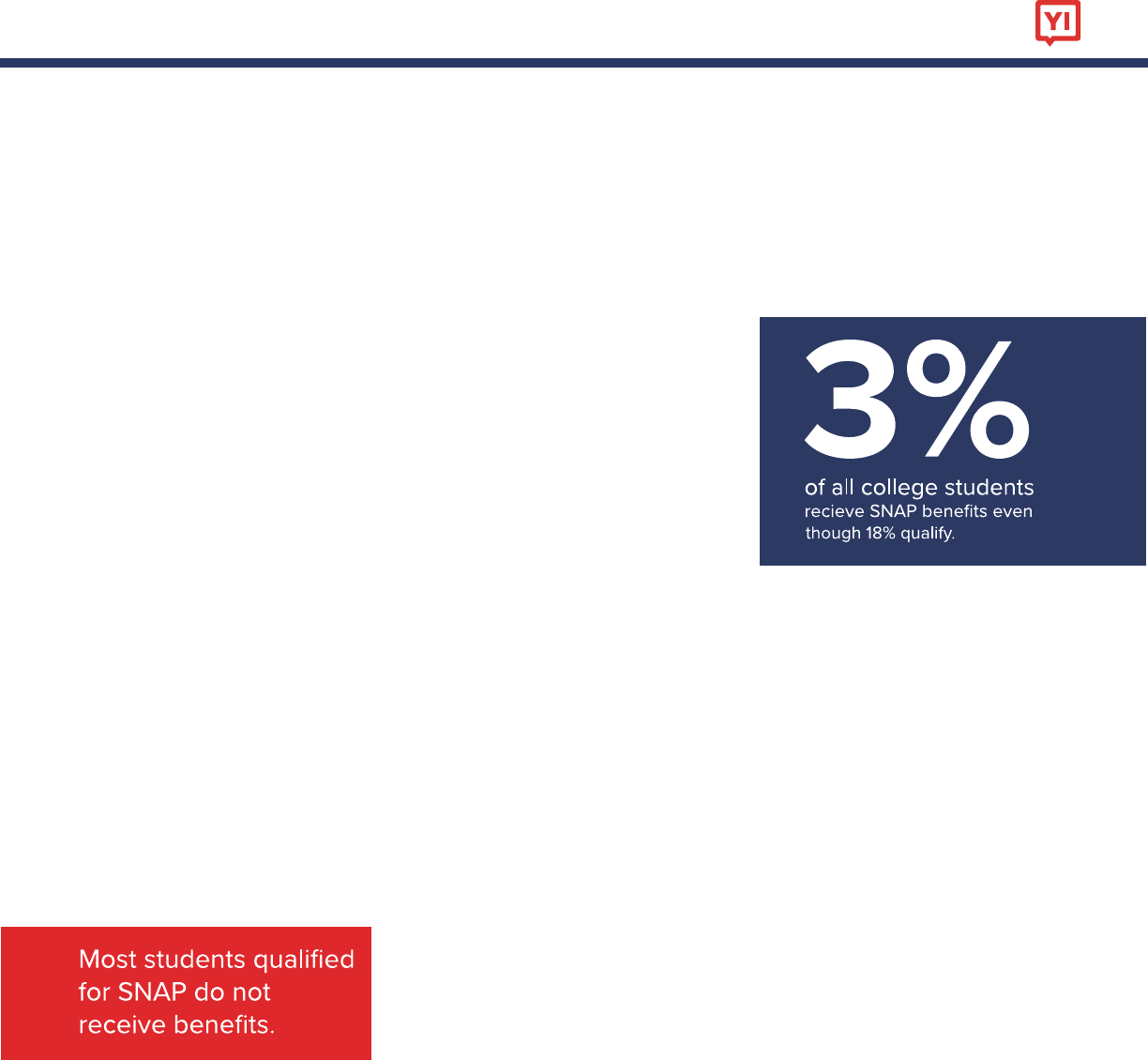

× Estimates show half of all college students experience food

insecurity; but only 18 percent are eligible for federal food

assistance (SNAP). Only 3 percent actually receive benefits.

× States are losing out on $4.2 billion in federal resources

they could be delivering to college students.

✓ We recommend the federal government simplify the

enrollment process and expand eligibility, and that states

and institutions improve outreach and coordination.

Rethinking SNAP Benefits

for College Students

February 2018 / Principal Investigator: Tom Allison

2

Hundreds of thousands of college students experience food insecurity every day, a condition characterized by disrupted

eating patterns and reduced quality and quantity of diets. The struggling, hungry college student subsiding on ramen

noodles or scouring for free pizza at on-campus events has permeated pop culture, but going hungry has deep physical,

emotional, and academic eects on students, and in some cases can prevent them from completing school entirely. Often

times, this problem can go unnoticed, especially since measuring student hunger requires students to self-report, and the

stigma around being unable to meet basic needs can keep students from seeking help.

Food insecurity carries serious consequences for student success. In one study,

the majority of students experiencing food insecurity reported missing classes and

study sessions, and not buying required textbooks.

1

Hunger also impairs cognitive

development into adolescence and adulthood, leading to poorer test scores and the

inability to fully engage in classes.

2

With roughly half of college students earning a

degree on time

3

, and serious disparities for African American and Latinx students

4

,

policymakers must consider campus hunger an integral part of our lagging student

success rates.

Over the past years, researchers and stakeholders have focused on food and housing insecurity as a significant challenge

for student success. The Wisconsin HOPE Lab found that 56 percent of community college students experienced low

or very low food security.

5

A consortium of groups similarly found that about half of community college students they

surveyed reported food insecurity in the last thirty days.

6

The Urban Institute estimated 11.2 percent of students at four-

year institutions and and 13.3 percent of community college students experience food insecurity, although those rates

represent a decline since 2012.

7

Despite these developments, researchers have yet to produce accurate measurements of the potential solution:

the number of college students qualified for and participating in federal food assistance programs. Also lacking are

statistically representative estimates at the state level. This matters because state factors facilitate federal food

assistance programs, in addition to playing a significant role in higher education policy. The research literature also lacks

statically representative estimates of SNAP eligibility and

participation by race and ethnicity (although Wisconsin

HOPE Lab disaggregates their surveys). This is important

considering the serious inequities in our higher education

system and that the trends could influence policy decisions

or outreach strategies to certain subpopulations.

8

Background

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students

3

This analysis identifies how college students could and should benefit from federal food assistance programs already

funded and in place. We estimate the number of college students who should qualify for federal food assistance, but do

not receive benefits. This shifts the approach from measuring hunger on campus, to rethinking how already available

federal resources can address the comprehensive aordability challenges facing today’s students. In this frame, we

see federal food assistance as a vehicle to move beyond traditional federal aid, and to help students achieve success in

college by helping them meet their basic needs.

The federal government sets the eligibility requirements for the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the nation’s largest food assistance program,

which oers monthly stipends to help low-income individuals and families pay

for food. Federal law allows states some policy flexibility, however.

9

For instance,

some states centralize their administration of the program, while others administer

at the county level. States have some discretion on what counts as income and

how household changes are reported.

Most college students are not eligible for SNAP unless they work twenty hours per week or receive a federal work study

grant.

10

Other exceptions include participation in programs under the Social Security Act, taking care of young children, or

placement in college through a workforce training program. Students who meet any of these exceptions might be eligible

as well.

11

In our analysis we consider the federal eligibility requirements for income and hours worked. Using a large, nationally-

representative survey of U.S. households, we estimate that 7.4 million college students earn household incomes under

130 percent of the federal poverty level ($15,678 for individuals; $31,980 for a family of four), the eligibility requirement

for SNAP.

12

This is not to say, however, that these 7.4 million impoverished students are actually food insecure. In fact,

most individuals in poverty are not food insecure (and most food insecure individuals are not in poverty).

13

SNAP eligibility also requires recipients to work at least part-time.

14

We estimate

about half of these low-income students, roughly 3.4 million students, also work

at least twenty hours per week and thus meet both eligibility requirements. These

3.4 million students make up only 18 percent of all college students despite reliable

estimates suggesting half of all college students experience food insecurity.

Only about 600,000, or 3 percent of all college students, actually receive federal food assistance. This means that the

vast majority of qualified students, 82 percent, do not receive federal food assistance. This sharply contrasts with the full

SNAP-eligible population, where 85 percent participated in SNAP in 2013.

15

Our Approach

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students

4

At an average monthly benefit of $125, a low-income student

participating in SNAP could receive a $1,500 food stipend

per year while attending college.

Added together, these 2.8 million students are leaving $350

million each month on the table, or a total of $4.2 billion per

year. This might seem like a dramatic number, but actually

would only result in an increase of 6 percent of SNAP’s total

cost in 2016.

16

While our dataset oers many promising benefits to

understanding student’s experiences with SNAP, it also

presents a few challenges. For instance, our estimates

simultaneously undercount and overcount eligible students,

and probably overcount the number of student beneficiaries.

We might be undercounting beneficiaries because our

dataset does not include indicators for exemptions college

students can claim to qualify for SNAP, such as participation

in other public assistance programs or caring for a family

member.

.

Our Approach, cont.

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students

Table 2. College students’ eligibility for and participation in

SNAP by state - 2015

Undergraduate students 19,000,000

Earning below 130 percent FPL 7,400,000

Earning below 130 percent FPL AND working

at least 20 hours per week

3,400,000

Receiving federal food assistance 600,000

Not receiving federal food assistance,

but should qualify

2,800,000

Average monthly SNAP benefit $125

Total monthly benefit of eligible students not

receiving federal food assistance

$350,000,000

Total Annual benefit $4,200,000,000

Total FY 2016 SNAP budget $70,911,550,000

Percent increase to cost of program 6%

Young Invincibles’ analysis of American Community Survey 2015 1-year estimates,

USDA Food & Nutritional Service

At the same time, our analysis might be overcounting the number of eligible students by including undocumented

students. The dataset used does not include an indicator for immigration documentation, and undocumented non-

citizens are ineligible for SNAP. Our dataset also does not include indicators of total assets, so our estimates might be

overcounting eligibility by including students who meet income requirements, but have too many assets to qualify,

although as discussed in the methodology section at the end of this report, we believe only a very small number of

students would be disqualified because of assets.

5

As this analysis does not measure food insecurity amongst college students but rather measures students’ qualifications

for and participation in SNAP, our findings indicate a problem of low take-up in the federal SNAP program.

17

We can

speculate the causes for this low enrollment: For starters, government resource web pages broadly disqualify college

students at the oset, and the complex web of exemptions and requirements for those actually eligible might impede

students’ ability to access the program. The social stigma of receiving federal food benefits likely also plays a role.

Below, we oer some recommendations for how the federal government, states, and institutions can increase SNAP

enrollment for college students through simplification, best practices from the field, and even expanded eligibility. Just as

how Medicaid expansion increased enrollment for individuals who were already previously qualified, expanding eligibility

for SNAP could encourage enrollment for the eligible college students currently not participating.

18

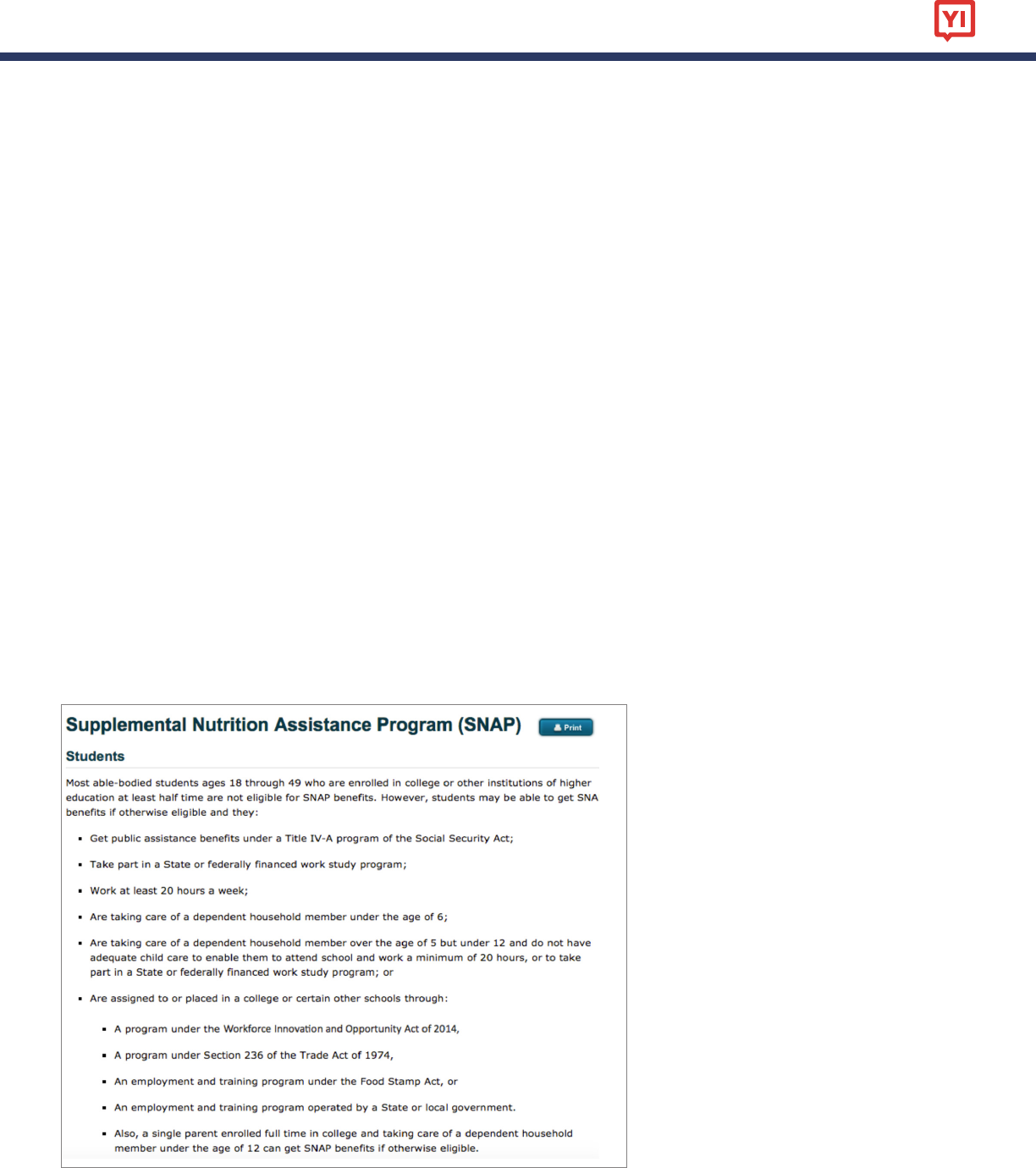

Federal Policy

The federal agency responsible for SNAP should improve how it communicates eligibility to college students. The first

sentence on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food & Nutrition Services’ (FNS) webpage explaining student eligibility

for SNAP states: “Most able-bodied students ages 18 through 49 who are enrolled in college or other institutions of higher

education at least half time are not eligible for SNAP benefits.” The next sentence lays out the other requirements. Rather

than disqualifying students at the o-set, FNS should change this language to say: “Individuals enrolled in college or

other institutions of higher education may be eligible for SNAP benefits, provided they:” This simple change would better

communicate to students that they might be eligible and motivate them to pursue enrolling.

The upcoming reauthorization of the Farm bill represents a unique opportunity to expand eligibility, simplify the

application process, and raise awareness

of SNAP. Congress should automatically

grant SNAP eligibility, with no work

requirements, to all students receiving a

Pell grant. Institutions would incorporate

SNAP enrollment information, with benefit

estimates based on that institution’s state,

into the financial aid award letters sent

to students. The Food & Nutrition Service

would coordinate with Federal Student

Aid to assign these qualified students

a unique code or identifier, not unlike a

discount code applied in online shopping,

that students could redeem with the state

or county agency responsible for certifying

eligibility. The code would remain valid as

long as the student receives the Pell grant,

eliminating the need for recertification. This

simplified process would reduce burden for

Recommendations

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students

Figure 1. Screenshot of FNS web page explaining college student eligibility for SNAP

6

the student and the state agency managing the program, and should increase participation.

Short of this bold, but common sense option, Congress should allow SNAP to treat Pell the same as the cash benefits

from other means-tested program like Supplemental Social Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or

General Assistance, that trigger categorical eligibility for SNAP.

19

In this scenario, participants would still have to comply

with other eligibility rules, including work requirements.

Currently, students enrolled in “Employment & Training (E&T) programs” qualify for SNAP without the work requirement.

20

While states have some flexibility in determining which programs constitute E&T, Congress should expand the definition of

these programs to include any sub-baccalaureate, career & technical education, or gainful employment programs.

The federal government allows states to request waivers for how they determine hours worked, with many opting to

average hours worked over the entire month. This benefits students who might take a week o from working during

exams or semester breaks, but still work enough hours during the rest of the month. This process could also be further

improved in the next Farm Bill, allowing states to track monthly averages or semester averages, to determine work

requirements, without a waiver.

The Department of Education should also improve measurements of food insecurity on campus. Wisconsin HOPE Lab

and the American Council on Education Center for Policy Research and Strategy have been asking for National Center on

Education Statistics (NCES) to collect more information about food and housing insecurity in the National Postsecondary

Student Aid Study since 2015.

21

Young Invincibles also recently submitted comments.

22

This would allow researchers and

advocates to gain a better understanding of where the problems are concentrated and to align interventions accordingly.

State Policy

State policy plays a significant role in increasing

SNAP enrollment for college students. A new

California law, conceptualized and advocated

for by Western Center on Law & Poverty, Swipe

Out Hunger, and Young Invincibles, awards

the designation of a “hunger-free campus” to

institutions with employees dedicated “to help

ensure that students have the information that

they need to enroll in CalFresh,” the state’s SNAP

program.

23

Young Invincibles identified these

solutions after convening listening sessions with

college students around the state. Other states

should similarly listen to the needs of college

students and develop solutions to meet their

basic needs.

Recommendations, cont.

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students

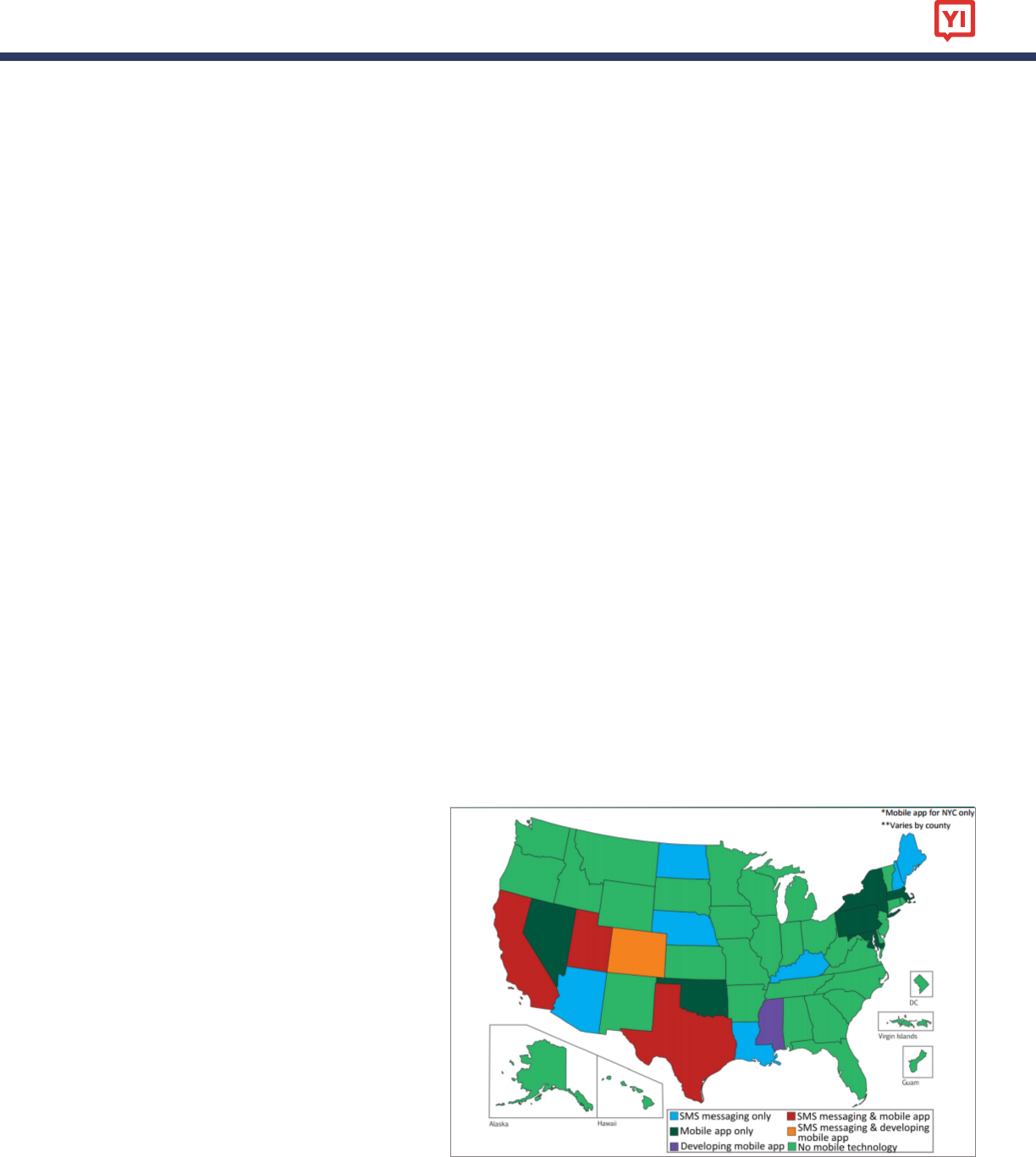

Figure 2. States with mobile platforms to manage SNAP benefits - From Food & Nutrition Services’ August 2017 State Options Report

7

All states should allow participants to apply and certify for benefits electronically. States should also develop mobile

platforms for participants to manage their benefits. Currently the majority of states, 35, have no mobile platform for their

SNAP program.

24

Only 33 states allow for online application and re-certification. Considering students’ busy lives and

young people’s use of technology, allowing for online recertification might reduce churn and increase enrollments.

States should also take advantage of guidance issued in a joint agency letter on aligning benefits to increase student

success, including using averaging weekly hours worked across the entire month and designating all career and

technical education (CTE) programs as equivalent to SNAP Employment & Training programs, which are exempt from work

requirements.

25

Institutions

To address this enrollment problem, institutions should ramp up eorts to inform their students of SNAP eligibility.

Institutions receive students’ financial information through the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, and

institutions could inform students whose financial information indicates they might be eligible for SNAP along with their

award letter.

Campuses can also adopt comprehensive case management programs, coordinating various benefits, including

participating in SNAP, for low-income students. Promising models include Single Stop and the Working Families Success

Network. These programs have demonstrated success in increasing retention and graduation rates for low-income

students.

26

Institutions can also learn from the Benefits Access for College Completion (BACC), an initiative that helped

community colleges systematically incorporate the patchwork of benefits for community college students.

Recommendations, cont.

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students

We welcome the higher education community’s recent focus on the comprehensive financial challenges facing today’s

students. The focus on the full cost of college, including food, housing, transportation, and other costs, is long overdue.

We should begin by considering how to help students who need the most help right now.

Fortunately, states and institutions can take advantage of existing law and funding structures, and provide nearly 3 million

additional college students with assistance meeting basic needs. Leveraging federal SNAP dollars to assist with basic

needs is a good place to start.

Conclusion

8

This analysis relies on the American Community Survey (ACS) 2015 1-year estimates, a large nationally representative

survey of households that includes roughly three million individuals. This large survey allows for statistically significant

disaggregated estimates of individuals’ income as percent of poverty level, college enrollment, participation in SNAP,

place of residence, and race and ethnicity. The sample does not measure food insecurity. The extract was compiled and

downloaded from IPUMS-USA (Steven Ruggles, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, and Matthew Sobek.

Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 7.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2017).

The organization of the ACS presents both challenges and advantages in measuring college students and federal food

assistance. While household is the unit of analysis, the survey also collects information about individuals, such as hours

worked and student status. This analysis defines poverty at the household level, with the number of household members

and their incomes factoring into the overall poverty level. This is an advantage, as students with low personal income but

high family income would not be flagged as in need.

However, food assistance participation is also measured at the household level, where if anyone in the household

receives food assistance, the entire household is indicated as receiving food assistance, regardless of whether the

student individually benefits. This possibly undercounts our estimates of students not receiving assistance.

To qualify for SNAP, one must possess less than $2,250 in total assets.

27

Unfortunately, total assets are not included in

the dataset used in this analysis. Research suggests that individuals who meet the income requirement, but have too

many assets, reduce SNAP eligibility by only 3 percent.

28

They also tend to be older, so may not be a significant factor

for college students.

29

We are also unable to measure other financial aid benefits these students might receive, although

those benefits tend not to play a part in SNAP eligibility determinations.

Our analysis might be overcounting the number of eligible students by including undocumented students. The ACS does

not ask questions about immigration documentation, and undocumented non-citizens are ineligible for SNAP.

ACS also lacks detailed education enrollment data, so we can only look at undergraduate and graduate students.

However, ACS asks a twelfth of their questions every month, thus alleviating the diculties presented by enrollment

churn throughout the year.

Methodology

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students

9

Methodology, cont.

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students

Table 2. College students’ eligibility for and participation in SNAP by state - 2015

Undergraduate

Students

Under 130% FPL Under 130% FPL

and works 20+ hours

Does not receive federal food

assistance (but qualified)

Percent

left out

Federal Funds

Left on Table

Alabama 260,000 120,000 60,000 46,000 77% $69,000,000

Alaska 41,000 8,722 5,000 5,000 100% $7,500,000

Arizona 390,000 150,000 74,000 59,000 80% $88,500,000

Arkansas 150,000 72,000 35,000 30,000 86% $45,000,000

California 2,700,000 900,000 320,000 250,000 78% $375,000,000

Colorado 320,000 130,000 73,000 65,000 89% $97,500,000

Connecticut 220,000 82,000 33,000 30,000 91% $45,000,000

D.C. 51,000 37,000 17,000 15,000 88% $22,500,000

Delaware 57,000 23,000 10,000 9,000 90% $13,500,000

Florida 1,100,000 370,000 160,000 110,000 69% $165,000,000

Georgia 580,000 230,000 97,000 76,000 78% $114,000,000

Hawaii 79,000 20,000 10,000 9,000 90% $13,500,000

Idaho 95,000 43,000 26,000 21,000 81% $31,500,000

Illinois 730,000 260,000 110,000 84,000 76% $126,000,000

Indiana 370,000 170,000 85,000 74,000 87% $111,000,000

Iowa 200,000 120,000 57,000 52,000 91% $78,000,000

Kansas 180,000 84,000 46,000 44,000 96% $66,000,000

Kentucky 220,000 100,000 56,000 47,000 84% $70,500,000

Louisiana 240,000 100,000 47,000 40,000 85% $60,000,000

Maine 68,000 33,000 18,000 14,000 78% $21,000,000

Maryland 370,000 120,000 52,000 44,000 85% $66,000,000

Massachusetts 450,000 220,000 100,000 95,000 95% $142,500,000

Michigan 600,000 240,000 130,000 100,000 77% $150,000,000

Minnesota 280,000 120,000 70,000 61,000 87% $91,500,000

Mississippi 170,000 85,000 35,000 27,000 77% $40,500,000

Missouri 340,000 140,000 72,000 61,000 85% $91,500,000

Montana 51,000 26,000 15,000 14,000 93% $21,000,000

Nebraska 115,000 59,000 34,000 30,000 88% $45,000,000

Nevada 150,000 40,000 21,000 16,000 76% $24,000,000

New Hampshire 77,000 35,000 20,000 17,000 85% $25,500,000

New Jersey 470,000 120,000 39,000 31,000 79% $46,500,000

New Mexico 130,000 48,000 23,000 15,000 65% $22,500,000

10

Methodology, cont.

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students

Table 3. College students’ eligibility for and participation in SNAP by race & ethnicity

Undergraduate

Students

Under 130% FPL and works

20+ hours

Does not receive federal food assistance

(but qualified)

Percent

left out

White, non-Hispanic 10,000,000 2,100,000 1,900,000 90%

Black / African American 2,900,000 530,000 350,000 66%

American Indian or Alaska Native 140,000 24,000 16,000 67%

Chinese 380,000 43,000 41,000 95%

Japanese 50,000 6,000 5,000 83%

Other Asian or Pacific Islander 980,000 110,000 91,000 83%

Other race 930,000 130,000 93,000 72%

Two major races 650,000 110,000 91,000 83%

Three or more major races 90,000 14,000 12,000 86%

Latinx 3,500,000 480,000 360,000 75%

New York 1,200,000 470,000 180,000 150,000 83% $225,000,000

North Carolina 580,000 250,000 110,000 88,000 80% $132,000,000

North Dakota 51,000 28,000 18,000 17,000 94% $25,500,000

Ohio 620,000 280,000 150,000 120,000 80% $180,000,000

Oklahoma 210,000 87,000 4,400 3,700 84% $5,550,000

Oregon 220,000 100,000 47,000 34,000 72% $51,000,000

Pennsylvania 680,000 320,000 150,000 140,000 93% $210,000,000

Rhode Island 81,000 39,000 21,000 19,000 90% $28,500,000

South Carolina 270,000 120,000 61,000 50,000 82% $75,000,000

South Dakota 44,000 22,000 14,000 12,000 86% $18,000,000

Tennessee 340,000 140,000 71,000 57,000 80% $85,500,000

Texas 1,500,000 510,000 240,000 190,000 79% $285,000,000

Utah 210,000 78,000 46,000 41,000 89% $61,500,000

Vermont 36,000 22,000 11,000 11,000 100% $16,500,000

Virginia 520,000 200,000 96,000 84,000 88% $126,000,000

Washington 380,000 150,000 63,000 50,000 79% $75,000,000

West Virginia 92,000 49,000 21,000 18,000 86% $27,000,000

Wisconsin 330,000 150,000 89,000 79,000 86% $118,500,000

Wyoming 31,000 14,000 9,000 8,000 89% $12,000,000

For media inquiries, you can contact Sarah Schultz at [email protected].

Visit our website for information regarding this topic & other related issues aecting young people:

younginvincibles.org

11

Sources

1

James Dubock, Brandon Matthews, Clare Cady, Hunger on Campus, October 2016, p 22, http://studentsagainsthunger.org/wp-content/

uploads/2016/10/Hunger_On_Campus.pdf.

2

Grace Jepkemboi, “The Eects of Hunger on Physical and Cognitive Development of Children,” chapter from Educating the Young Child, October

2017, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-62887-5_10.

3

S.A. Ginder, J.E. Kelly-Reid, and F.B. Mann, Graduation Rates for Selected Cohorts, 2008–13; Outcome Measures for Cohort Year 2008; Student

Financial Aid, Academic Year 2015–16; and Admissions in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2016: First Look (Provisional Data) (NCES 2017-150rev).

U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch.

4

Emily Tate, “Graduation Rates and Race,” Inside Higher Ed, April 26, 2017, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/04/26/college-

completion-rates-vary-race-and-ethnicity-report-finds.

5

Sara Goldrick-Rab, Jed Richardson, and Anthony Hernandez, Hungry and Homeless in College, Wisconsin HOPE Lab, March 2017, http://

wihopelab.com/publications/Hungry-and-Homeless-in-College-Report.pdf.

6

James Dubick et al, Hunger on Campus, 7.

7

Kristin Blagg, Assessing Food Insecurity on Campus, Urban Institute, August 2017, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/92331/

assessing_food_insecurity_on_campus_0.pdf.

8

Tom Allison & Chris Nellum, Race & Ethnicity as a Barrier to Opportunity, Young Invincibles, February 2027, http://younginvincibles.org/wp-

content/uploads/2017/05/Higher-Education-Equity.pdf.

9

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition Service, State Options Report, October 2016, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/

snap/13-State_Options-revised.pdf.

10

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition Service, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP):

Students”, accessed February 2, 2018.

11

Ibid.

12

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition Service, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Am I Eligible for SNAP?”,

accessed February 2, 2018, https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligibility.

13

Feeding America, “Poverty and Hunger Fact Sheet,” September 2017, http://www.feedingamerica.org/assets/pdfs/fact-sheets/poverty-and-

hunger-fact-sheet.pdf.

14

Amy Ellen Duke-Benfield, Bolstering Non-Traditional Student Success, CLASP, 8, December 2015, https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/

public/resources-and-publications/publication-1/Bolstering-NonTraditional-Student-Success.pdf.

15

Dottie Rosenbaum and Brynne Keith-Jennings, SNAP Costs and Caseloads Declining, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 2016,

https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-costs-and-caseloads-declining.

16

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition Service, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Costs”, accessed

February 2, 2018, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/pd/SNAPsummary.pdf.

17

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition Service, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Students”, accessed February 2,

2018.

18

Vikki Wachino, Samantha Artiga, and Robin Rudowitz, How is the ACA Impacting Medicaid Enrollment, The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation,

May 2014, https://www.k.org/medicaid/issue-brief/how-is-the-aca-impacting-medicaid-enrollment/.

19

USDA, State Options Report, 20.

20

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition Service, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP):Employment and Training”,

accessed February 2, 2018, https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/federal-jobs-training-programs.

21

Wisconsin HOPE Lab, et al, “Request to Add Measurement of Food Insecurity to the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study,” August 2015,

http://wihopelab.com/publications/NPSAS%20Brief%202015_WI%20HOPE%20Lab_ACE.pdf.

22

Comment on the Department of Education (ED) Notice: Agency Information Collection Activities; Proposals, Submissions, and Approvals:

Agency Information Collection Activities; Comment Request; 2017-18 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study Administrative Collection

(NPSAS:18-AC).

23

AB-453, Postsecondary education: student hunger, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billCompareClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB453.

USDA, State Options Report, 25, 28.

24

Joint Agency letter, “Aligning Federal Supports and Program Delivery for College Access & Completion”, November 15, 2016, https://www2.

ed.gov/documents/press-releases/federal-supports-college-access-completion.pdf.

25

William N. Evans Melissa S. Kearney Brendan C. Perry James X. Sullivan, Increasing Community College Completion Rates Among Low-Income

Students, National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2017, http://www.nber.org/papers/w24150.pdf.

26

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits, September 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/a-quick-

guide-to-snap-eligibility-and-benefits.

27

United States Department of Agriculture, Urban Institute, Asset Limits, SNAP Participation, and Financial Stability, 9, https://fns-prod.azureedge.

net/sites/default/files/ops/SNAPAssets.pdf.

28

Ibid.

Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students